(delivered March 15, 2018 to The Department of English, University of Ottawa)

In October 2016, a 24 year-old man, Ryan Stanislaw was arrested by police in his hometown of North St. Paul Minnesota. He had shot through a neighbour’s window with his AR-15, a semi-automatic assault rifle. When questioned by authorities, Stanislaw explained that he had been defending the neighbourhood from zombies. He had shot at zombie at the end of the road, but had missed, inadvertently putting a bullet into the bedroom wall of one sleeping Kenneth Quale. In his statement, Stanislaw said that, in the absence of a police presence, he had taken it upon himself to “protect the neighbourhood.” “I figured I’d do something,” he said.

Now, most people would argue that the only threat in St. Paul that night was Stanislaw himself. But Stanislaw was seeing zombies. And, indeed, nothing better justifies skulking about a residential neighbourhood at night with a loaded assault rifle than an incursion of the ravenous undead. It makes sense. I myself have played out a similar scenario in my mind on countless occasions. However, I don’t own an AR-15. Ryan Stanislaw was not supposed to own one either as he had a prior conviction for uttering terrorist threats and was prohibited by law from owning a firearm.

According to the NRA there are an estimated 3 million AR-15s in circulation in the US. It has been branded by the NRA as “America’s Rifle.”

The AR-15, of course, is the same weapon that was used most recently in the Parkland, Florida school shooting that saw 17 people killed. In 2012, Adam Lanza used an AR-15 to murder 20 school children in Sandy Hook. Stephen Paddock modified his AR-15 with a bump stock that enabled him to dispatch 58 country music fans from a hotel window in Las Vegas last year. A month after that, Devin Kelly murdered 26 people in a Texas church with a similar weapon. The connection between the AR-15 and mass murder goes back to 1982, when it was used by a man named George Banks to kill 13 people in Pennsylvania, including 7 children.

I’m trying to draw attention to a constellation of events, objects, and attitudes that connects these mass shootings to the zombie’s current status as a privileged figure in the cultural imagination of the west and to the plot of the zombie apocalypse as a paradigmatic narrative structure for our times.

If the vampire is a serial killer who stalks his victims one by one, the zombie, on the other hand, belongs to the world of mass shootings. Dracula and Jack the Ripper arise in same social context, a world that reached its nadir in the 1970s and 80s with Son of Sam, Charles Hatcher, and Ted Bundy. I’m reading the paper this week about Bruce McArthur, the gardener in Toronto who’s killed at least 7 people since 1990, and all I can think is ‘how old-fashioned!’ There’s a reason why current serial killer stories are all period pieces. But nothing quite speaks to our current historical moment than the mass shooting, and it is in this same context that the zombie narrative reaches something of a fever pitch. Not Jack the Ripper, but Anders Breivik. Not Salem’s Lot, but The Walking Dead. The zombie horde is a killing mass, but in the lone gunman dispatching scores of hapless victims in a single session we find a model of the apocalyptic survivor whose capacity for massive violence is transformed within that fantasy into a virtue. Running like a thread connecting the historical reality of mass murder and the cultural obsession with zombies is the AR-15.

I don’t put much (bump) stock in the argument that video games turn children into killers. But I do know how satisfying it is to find an AR-15 when I’m playing a zombie-themed first-person shooter or survival horror game. I drop the crowbar or machete I’ve been using and pick up the AR-15 with its 20 round clip and I go to town on those zombie bastards. And as long as I can keep finding ammo, I am a veritable killing machine at the same time that I get to be a hero, the good guy. Just like Ryan Stanislaw protecting his neighbourhood, making himself useful.

I’m not a psychologist, but it’s not too hard to imagine that the mass killers I’ve mentioned might have seen their victims in the same way Stanislaw saw the man at the end of the street, or as I see the zombies when I’m playing Dead Island—as something monstrous, something perhaps less than human, as something walking and talking but somehow dead inside, or simply something so obviously 2-dimesional that its death is likewise unreal.

But its even easier to imagine how the zombie enables a fantasy of heroism, virtue and usefulness that does not oblige us to question or rethink much of the prevailing ideological and technological machinery of 21st century life—even as zombie narratives continuously rehearse the end of times. Whatever I go on to say about zombies and zombie stories, we have to start with the idea that the contemporary zombie and its enplotment represents a complex wish fulfillment; despite its obvious horror, the zombie novel, film, or videogame speaks to a kind of craving on our part for change, even catastrophic change, but also for the emergence of conditions in which some very old fashioned and increasingly embattled ideals can reassert themselves and reacquire a futurity that now seems lost.

There can be no doubt that the bulk of zombie narratives are socially conservative, masculinist, and tied to certain old-timey notions of community. But they also register a protest against the tendencies of late capitalist culture that appeals to people across the broadest political spectrum. Because the one thing that I have in common with a gun-loving Christian misogynist is the sense that the world is circling the drain, and it may be this fact that explains how we can both of us be so hungry for zombie narratives and their various consolations.

There is a tradition of the zombie that reaches back to Africa and the colonial West-Indies and to pre-abolition America, but over the last 40 years, the zombie has acquired a set of characteristics and associations that set it against that tradition to such an extent that we can speak of the contemporary zombie as a distinct entity. I propose, therefore, that we read the contemporary zombie as a postmodern trope and the zombie narrative as an historically specific cultural symptom, one that expresses both the desires and the anxieties of late-capitalist culture. In other words, I propose that we treat the contemporary zombie phenomenon as having produced texts that do what any fictional narratives do: namely, provide “imaginary or formal ‘solutions’ to otherwise irresolvable social contradictions” (Jameson, The Political Unconscious).

What I’m trying to say is that whether we’re mentally ill or not, the zombie narrative makes sense for us today. It’s become a major tool for what Fredric Jameson calls our “cognitive mapping”: it helps us apprehend the world and our place in it; but at the same time, it inevitably registers the effects of social conditions it can never transcend. Some zombie narratives and some figurations of the zombie are more critically useful or telling than others, but all zombie stories, by virtue of their very existence, tell us that there is something there is that needs figuring out.

ZONTOLOGIES©

But first we need to figure out what we mean when we use the word “zombie.” One of the problems with talking about the “nature” of zombies is that they don’t exist. You can get in some pretty intense arguments with people about what does or does not count as a zombie. Unless you take a step back and acknowledge that, as imaginary constructions, zombies are under no obligation to conform to a set of prescribed rules, you can end up in the world’s dumbest fistfight.

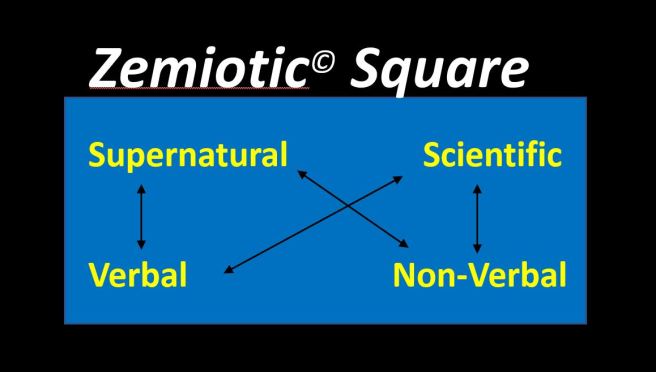

But we can learn a great deal about the function of the zombie in our cultural narratives from debates about its ontology, its nature. Historically, attempts to define the zombie have produced many disagreements, but I’d like to argue that the zombie occupies a space framed by 2 binary oppositions in particular. First, the zombie is either a supernatural entity or it’s a scientific one. It is either a species of magic that causes a dead body to get up and eat your face, or the causes are natural and empirical. In the first instance, you’d call a priest or a shaman to help with your zombie problem; in the second, you’d call a doctor or scientist. The second opposition is this: the zombie will either speak or be capable of speech or it will be entirely non-verbal, capable only of growls, groans, and other guttural noises. In the first case, you have a zombie with a degree of self-consciousness and capable of development; in the latter, you have an entity that is, as David Chalmers puts it, “all dark inside.”

Putting these oppositional pairs together, we can form a ‘zemiotic’ square that enables us to determine the distinct zombie types, after which we can make inferences about the meaning and the function of the zombie based on which of these types dominates in any historical or cultural context.

Following the arrows, you see that we end up with 4 general types of zombies: We can have

1) supernatural verbal zombies

2) supernatural non-verbal zombies

3) scientific verbal zombies

4) scientific non-verbal zombies.

Generally speaking, there has been an historical trend away from supernatural causes towards scientific ones. We also notice a general trend away from verbal zombies to non-verbal zombies. But any of these figurations remain possible at any given time.

SUPERNATURAL VERBAL

Before the zombie became an index of environmental and biological concern—in other words before it functioned in cautionary tales about radiation poisoning, toxic waste, bioengineering and the like, it was a creature of magic. It shared a mental space with ghost and ghouls and other demonic creatures.

This was the mainstream tradition in comic books, pulp novels and movies prior to Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, released in 1968, which attributed the zombie plague to the effects of a crashed satellite, thereby shifting the bias from occult to scientific explanations. But there are still examples of this sort of zombie in contemporary culture, but they are often overtly allusive to an outdated comic book tradition: as in the Simpsons Tree House of Horror bit and in the zombies attending the “Unholy Masquerade” in What We Do in the Shadows. The Deadites of Evil Dead are a kind of zombie, animated by satanic forces, but like most zombies of this type now, they are played for laughs.

SUPERNATURAL NON-VERBAL

More common than supernatural verbal zombies are the supernatural non-verbal kind, though these too are less in evidence today than either of the next two types. Arguably, the zombie tradition begins with supernatural non-verbal zombies, in the form of the Haitian ‘zombi,’ a resurrected plantation worker forced back to work in the cane fields. Obviously, the Caribbean voodoo zombie is a rich figure for political analysis and a number of books have recently come out that read the voodoo zombie and its cultural reverberations in the context of postcolonialism and ‘black Atlantic’ history. I find this work fascinating, but I’m suspicious of approaches that insist that all zombie stories be read in this context.

My own view is that while some contemporary zombie narratives allude to or resonate with this history, most are energized by a different matrix of historical concerns. Furthermore, there is a tendency in postcolonial readings to conflate or ignore the ontological difference between supernatural beings and natural-scientific beings that tends to obscure the cultural work being performed by the currently dominant type, the scientific non-verbal zombie. But we still see versions of the supernatural non-verbal zombie in films like Poltergeist, which tells us that we shouldn’t pave over cemeteries to build suburban planned communities, and in Games of Thrones whose ‘white walkers,’ technically wights, could be read as zombies of a kind.

OBJECTS OF SCIENCE

For the most part, when we talk about zombies today we assume a scientific cause. The general disappearance of the supernatural zombie is in itself a telling fact. In the late 1930s, the American writer Zora Neale Hurston—most famous today for her contribution to what’s become known as the Harlem Renaissance—went to Haiti to collect folk tales. During her stay she had occasion to meet a woman reputed to be an actual zombie. Felicia Felix Mentor had passed away, and was then raised from the dead by a voodoo priest, and now passed her days in a near vegetative state in a Port Prince mental asylum.

I had the rare opportunity to see and touch an authentic case. I listened to the broken noises in its throat…. If I had not experienced all of this in the strong sunlight of a hospital yard, I might have come away from Haiti interested but doubtful. But I saw this case of Felicia Felix-Mentor which was vouched for by the highest authority. So I know that there are Zombies in Haiti. People have been called back from the dead. (Hurston, Tell My Horse, 1938)

Hurston was a trained anthropologist, but her report was ridiculed by the academic and scientific community who were unwilling to believe that Mentor’s condition was a result of voodoo magic. I’m sorely tempted to explore the reasons why Hurston was willing to believe in the supernatural explanation. But for our immediate purposes, I’ll simply suggest that we might read this anthropological faux pas and its resultant controversy as marking the historical moment when the figure of the zombie is forced to leave the real world of history and enters the world of fiction where it has steadfastly remained, sightings in North St. Paul Minnesota notwithstanding.

My point is this: whereas it was at one time possible to imagine an outside to the dominant model of life in which science and rationality are the final arbiters of reality, whereas it was still possible in some places to live a reality where there were zones of experience not subject to rationalist explanation, those zones and that outside have disappeared in the context of globalization in which there is no outside whatsoever. The negation of the historical zombie speaks to the loss or negation of that outside. To some extent we can see the bonanza of fictional zombie narratives and other fantastical stories as an attempt to compensate for that loss. And to some extent we can see how many of these stories attempt to trouble the idea that scientific rationality is only ever adequate to experience. But the truth is that the lion’s share of zombie narratives work to shore up the hegemony of science and rationalistic instrumentalization first, by virtue of their very fictionality, and second because they will attribute scientific causes and explore pragmatic solutions to their zombie problem.

The contemporary zombie is an object of science. The zombie plague is a natural phenomena, which seems paradoxical because the zombie is a scientific impossibility. But it’s natural in the sense that its origins are not magical or otherworldly but demand a scientific investigation and solution. It’s no accident that the CDC, the American Centre for Disease Control, figures so prominently in many contemporary zombie narratives. Whereas one of the heroes of the 1932 film White Zombie, the first zombie movie, is a Dutch-reform minister, the hero of the film adaptation of World War Z from 2013 is an agent for the World Health Organization.

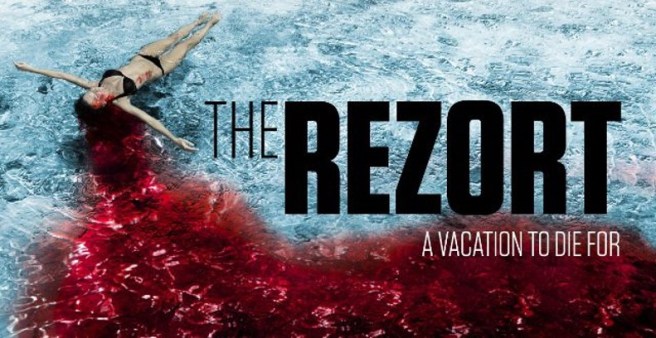

Though some films will attribute the zombie fact to alien interference, radiation, chemical agents, or genetic manipulation, far and away the most prevalent explanation of the zombie plague in contemporary narratives is some form of virus. It’s a virus that animates the zombies of The Walking Dead. It’s a virus in 28 Days Later, which after The Walking Dead is probably the most influential zombie text of the last 30 years. It’s a virus in the Spanish REC films, in The Rezort, The Dead, Dead Before Dawn, Extinction, The Horde, Here Alone, Maggie, Open Grave, Quarantine, Sean of the Dead, Warm Bodies, and Zombieland—to name but a few. An interesting deviation from the typical virus plot is found in The Girl with All the Gifts, where a fungal infection is responsible for the zombie plague. But even here the result is the same: uncontrollable cannibalistic urges.

The old voodoo zombie was raised from the dead by a shaman who retained control over the monster. There was no sense that the zombie craved human flesh nor, importantly, that it could produce more zombies. But in the contemporary zombie story a bite from a zombie will turn you into a zombie, and this trope is more or less consistent across the board even when the condition is not viral in nature. The modern zombie, in other words, is a figure of contagion and disease. And it seems pretty obvious that it resonates with historical events like mad-cow disease, the SARS scare, ebola and the like—diseases which become more threatening the more interconnected and mobile the world becomes.

Of course, vampires also make new vampires by way of biting victims, but the vampire can discriminate: he or she can choose which victims will be invited into its aristocratic circle and which are destined to be mere snacks. The zombie, and this is a crucial aspect of its depiction, cannot make choices, it cannot discriminate or plan. You can’t reason with it any more than you can reason with the flu, or cancer. Totally lacking any interiority or psychological depth, the zombie is neither an ethical nor a political subject. It is an absolute other whose only job is to be killed.

That is, unless it is capable of speech. Though the bulk of contemporary zombie narratives feature non-verbal and unthinking antagonists, a significant number portray zombified characters whose linguistic and cognitive functions are not entirely compromised. A lot of people will tell you that the chief distinction between zombies relates to their mobility: the internet is full of heated debates about fast vs. slow zombies; many feel that the zombie capable of sprinting is a kind of travesty, a violation of the ground rules of the zombie genre. Another controversy relates to the difference between properly undead creatures and human beings who have contracted a disease that turns them violent or cannibalistic. These differences can indeed be crucial, but neither a zombie’s degree of mobility nor the specific nature of its vitalism determines its meaning for us quite so much as whether it possesses language or not. In the context of the mainstream contemporary zombie narrative, talking zombies and non-talking zombies entail completely different narrative possibilities, and serve very different cultural functions.

SCIENTIFIC VERBAL

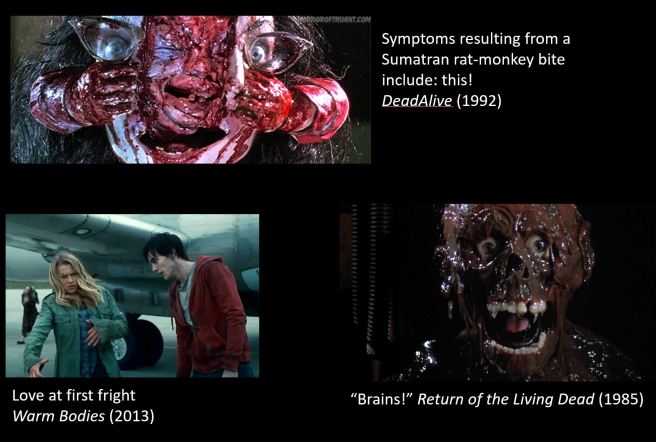

Talking zombies appear more frequently in Zombie comedies (eg. Return of the Living Dead: “More brains!”) which in itself suggests that speech robs the Zombie of the abjection and existential terror it might otherwise elicit.

In fact, a ‘zomcom’ like Warm Bodies—which not only depicts Zombies engaging in (admittedly limited) discourse but features a Zombie narrator with a rich interior life—constructs Zombies as a social class rather than a species of the un-human. Figured as a member of a subaltern group or community, the Zombie can then serve a variety of plots revolving around the question of rights and privileges, prejudice, conformity, decorum, and so forth. These plots would seem to require that the Zombie speak, but with an accent—like an Italian or Arab. Romero’s Land of the Dead is an obvious example of Zombies as “multitude” or lumpen proletariat. Similarly, in 2006 film Fido, zombies have been domesticated and serve as the worker class performing menial labour in a waspy 1950s style American small town. Here, there does seem to be a clear allusion to the zombified worker of the Hatian tradition, but with the modern twist that the zombies are also infectious and prone to rampage when not subdued by their shock collars.

At the other end of the spectrum, The Santa Clarita Diet is a morose comedy of manners where being a Zombie amounts to little more than an especially complicated lifestyle choice. Connecting these two films, however, is the Zombie’s capacity for speech, which, in individual terms, makes it possible to have a Zombie protagonist and, in social terms, makes it possible to imagine something like Zombie activism. When the zombie speaks, the axis of identification is skewed towards the zombies and away from the survivor community; the political work of these zombie films depends on the audience’s ability to sympathize with their plight, and this seems to depend on the zombie’s ability to articulate its unfair treatment. These movies tend to work exactly like the latest cycle of Planet of the Apes movies which propose an inclusive community across the ontological divide between animal and human, but require that the animal speak to make this a thinkable possibility. A variation of the zombie as subaltern theme can be found in films like the Canadian-made Afflicted and the The Cured, an Irish film that stars a Canadian, Ellen Page, in which a cure has been developed for zombie-ism and the formerly mindless rapacious cannibals that ate your sister and father must struggle to reintegrate into a society that, understandably, has trust issues. We have the same themes of othering and prejudice that we see in Warm Bodies, Fido, and the Romero cycle of films, but within a truth and reconciliation framework.

SCIENTIFIC NON-VERBAL

Which brings us to the contemporary mainstream tradition of the scientific non-verbal zombie. What can we say about this type? Well, there seems to be a connection between its lack of speech, its contagiousness, and its tendency to congregate. To be capable of speech is to be capable of individuation, of having a self and setting that self in opposition to the mass. The Santa Clarita Diet and I-Zombie, for instance, are stories about personal struggle and there is no massification of the zombie that poses an existential threat to humanity.

The mainstream zombie—the zombie apocalypse zombie—demonstrates a desire to assemble. The lone zombie always risks looking comical or pathetic. As such, it is always the zombie herd, the horde, which threatens the survivor. And it is with the survivor and the survivor community that the viewer or reader is asked to align herself.

The Zombie’s power to transform the physical and social landscape lies in the possibility of its becoming plural. It is the survivor’s inclusion within that group that she most dreads. More than the loss of those forms of society to which she is accustomed, the survivor is tormented by the idea of her incorporation into a collectivity the only law of which is her loss of individuality and self-awareness. The Zombie is less a thing, than a process: pure interpellation without remainder.

In his book, Zombies: A Cultural History (from which I learned about Hurston and Felix-Mentor, discussed above) Roger Luckhurst suggest that the zombie is “one of the exemplary allegorical figures of the modern mass” (109) and points out that many zombie narratives are overt commentaries on the modern process of massification itself (129). Critics are split on whether the zombies represent the revolutionary potential of the mass or whether they represent the death of politics itself. Romero’s own films are themselves somewhat ambivalent on this question.

There’s a famous moment in his Dawn of the Dead, when the zombies are pounding on the doors of the shopping mall in which the survivors have taken shelter and one of survivors asks “who are they, what do they want”? To which she gets the response: “They’re us, that’s all.”

On the one hand, Romero’s Dawn of the Dead is a fairly obvious allegorical critique of consumer capitalism and the viewer is explicitly invited to read the zombie horde as a hyperbolic representation of who we already are: in this sense, the zombie works to figure the generalized subject of capitalism. In its stupidity, we can read both the decline of the general intellect and the narrowing of reason in the public sphere. In its mindless sociality we can recognize a tendency towards group think and social conformity. Also, the zombie is perpetually hungry. I have yet to see a movie that depicts a satisfied zombie passing up on a meal because it’s already full. And yet, it doesn’t need to eat to live: in the absence of food, a zombie just keeps going. As an entity who craves what it does not need, the zombie can be read as an analogue of the contemporary consumer. I don’t think it’s an accident that the zombie emerges at a time of plenty and excess in North America and the rest of the west. It seems a fitting monster for a culture in which obesity and not emaciation is the sign of poverty. I would go so far as to surmise that a culture still in the grips of genuine hunger will never produce a zombie film. The zombie is the demonic and disreputable flipside of foodie culture.

So, there is this strong tradition of politically self-conscious zombie narratives in which the zombie horde mirrors the dysfunctions of contemporary global capitalism which produces wealth in direct proportion to the destruction of our intellectual, emotional, and physical well-being. Fredric Jameson coined the term “waning of affect” to describe the flattening of our emotional range in the context of the media society where only shock horror and pornography manage to produce a response beyond that suitable for the workplace. And its true that nothing shocks a zombie. The great thing about zombies is that they can manage to look bored while eating a baby.

On the one hand, as I said, Romero’s films convey the message that the zombies ‘are us’ in the sense that they represent what we have done to ourselves and to our fellow citizens. But on the other hand, the zombies are also the disenfranchised “them” that call on a more privileged “us” for recognition and inclusion as we see in Romero’s Land of the Dead. This seems to be the point of the film the REZORT, in which zombies are hunted for sport on a vacation island for rich people and we eventually discover that the stock of zombies is continually replenished by refugees from displacement camps located on the other side of the island.

This sort of political critique is benignly posthumanist in its assertion that coalitions can be formed across the traditional distinctions between life and death, human and animal, but that it may take a form of violence to encourage this sort of recognition.

In this context, it’s interesting to note the number of films and books in which early zombie outbreaks are reported in the media as “protests,” “riots” or “civic unrest.” In the South Korean film Train to Busan, zombie violence is initially thought to be the result of striking workers unhappy with their working conditions. For the economic juggernaut that is South Korea, the idea of a general strike is actually more terrifying than a plague of zombies, who will never present a list of demands.

But there is certainly something going on in this obsessive return in zombie narratives to an idea or image of the mob. The zombie horde is repeatedly represented in ways that invite comparisons with unruly political assemblies: protests, riots, marches, and the like. As mobs, Zombies demonstrate the liquidating power of collective action. The Zombie film, we might say, exposes the true significance of any political manifestation which lies not in the speeches that precede, follow and punctuate the physical exercise, but in the sheer fact of bodies in concert. The zombie horde is, after all, a mass. As a mass, it interrupts the flow of commerce and overwhelms civic infrastructure.

But at the same time, the Zombie horde manifests for nothing. If zombie hordes represent collective action then it’s a collective action devoid of purpose, motivation, or calculation. Zombie assemblies, then, while seeming to imitate a form of political intervention, actually constitute an inversion of politics: history turned into nature, the end of history. In this respect, they are the truest representation of the mass today and its pointless, misdirected moments of violence. The Zombie horde is a soccer mob, a hockey riot.

Having said that, the zombies do bring about change, radical change. The propagation of the Zombie narrative world wide, its own virus-like spread across the globe, is an indication, firstly, that late-capitalism has succeeded in making it possible to speak of a world culture and, secondly, that such globalism carries within it an unconscious desire to see itself destroyed. The truth is, zombies are a billion dollar idea because some part of us wants the apocalypse to happen. 3 million AR-15s in America cry out for a reasonable excuse to exist.

But in the sense that, even in fiction, it is an accident of nature that accomplishes what politics to this day has been unable to do—that is to say, transform human relations and our relationship to the natural world—the Zombie apocalypse projects the fantasy of a non-political redemption of human society. It as though the very poverty of our democratic institutions, the deepening realization that protest and critique are powerless against institutionalized stupidity and greed, the undermining of evidence-based decision-making, the increasing impossibility of informed debate, the collapse of the university as a space for complex thought, the expanding power of corporations, the erosion of public space, the proliferation of distracting technology, have all collectively given birth to a fantasy of social change without politics, without the labour of activism, without speech. Symbolically, the zombie plague delivers us from the paralysis of our historical moment; it does so on our behalf because we can no longer even imagine how we might accomplish this ourselves.

In the dominant tradition of the scientific non-verbal zombie we are not meant to identify or sympathize with the zombies. But they are our friends. The Zombie event is not a disaster, it is a gift. The zombie apocalypse provides an opportunity to imagine how things might be otherwise. Except in those few instances where the Zombie contamination is limited to a single municipality (or island or hospital), the transformation of society is global and irreversible. To renew itself at all, human society must organize itself according to a different logic than that which dominated prior to the disaster—which means, in effect, discovering alternatives to the nation state, wage labour, private property, monetary exchange, jurisprudence, not to mention the less formalized systems governing gender, sexuality, race and ethnicity. There’s a reason why every survivor group is a heterogeneous mixture of representative types that looks like a Gov’t of Canada P.S.A. for multiculturalism.

It is for this reason that even the most disturbing and traumatic versions of the Zombie plot betray some affection for their disaster: in the very liquidation of everything we are supposed to hold dear there dwells an otherwise unrealizable political possibility. This is what I meant when, following Jameson, I argued that the Zombie narrative presents an imaginary solution to irresolvable social contradictions. It realizes change in fiction because we live in a world where the hope for change is increasingly imaginary. And it provides a framework in which to entertain as entertainment alternative models of human interaction and the good life. Think of the utopian impulse of World War Z [the film] that reconstructs the world according to the principles of humanitarian internationalism presided over by the WHO and the UN; the pastoralism of the ending of 28 Days Later; The Walking Dead has been nothing but a yearly exploration of competing models of community and political organization the general trend of which seems to be towards some form of anarcho-communism, which for the last two seasons it has set against the fascism of Negan and the Saviors. In most zombie narratives, the end of history takes a comic form insofar as the destruction of tradition is only partly unwelcome.

That’s at the social level. At the level of the individual subject, the zombie narrative constructs for him or her a meaningful life, or at least the possibility of discovering what a meaningful life is. Think of Daryl in The Walking Dead; had the Zombies not appeared and changed everything, he would have ended up a drug dealing scumbag like his brother. The Zombies made him a better man.

Why do I like zombies so much?

Surely, my appetite for zombie films, games, and books has something to do with the fact that the definition of courage in my own life is disagreeing with someone on Facebook. It’s got to be related to the fact that there’s nothing about my manly strength—in quotation marks—that puts me at an advantage in an information-based economy. The fact that I want to live in a community, but I merely function in a society, no doubt has something to do with it. It may well speak to the fact that I’d rather make what I need than buy it, but I don’t have the skills or the time. Maybe it has something to do with my recurrent feeling that teaching young people about the poetry of P.K Page is a meaningless, even obscene, way to make a living. I live a life my grandfather could only have dreamed of, in which I have everything I need, and almost everything I want, and yet I’m often bored to death. More and more, I feel a general sense of guilt I can’t seem to shake. Perhaps I want to be redeemed.

It comes down to this: While there are some zombie narratives that are politically self-conscious and purposely use the genre to satirize or critique contemporary society, most zombie narratives are escapist fantasies that work for us because they secretly speak to our own unconscious need for an existence more meaningful than the one we actually lead. Some zombie narratives skew left, others skew right. But there’s a profound dissatisfaction and visceral longing that connects millions of people who would otherwise have nothing in common, just like the fictional Zombie event brings together people who would never have interacted, let alone come to love one another, in their old world. We use the term “zombie apocalypse” all the time now without remembering that the word apocalypse does not mean disaster, but revelation. My own foray into the world of zombies began as a semi-serious pass time, but the more I’ve looked, the more they have revealed to me the failings, the fears, but also the hopes of our contemporary world.