Presented at Concordia University’s SpokenWeb Symposium on “Listening, Sound, Agency,” May 21st 2021.

Today, I want to talk about zombie sounds. There’s a visual bias to most discussions of the zombie in popular culture. Fan discussions often focus on the special effects that are involved in representing the undead in their various states of decay; zombie makeup artists and effects coordinators like Tom Savini and Greg Nicotero are often better known than the directors on whose projects they work. More theoretical discussions—there is now a whole field of zombie studies—will often invoke affective categories like disgust or abjection but generally focus on the same visual elements that signify the repulsive body.

Of course, the zombie is a uniquely visual monster; it’s a creature of comic books, and film, and television and video games. It doesn’t have the literary provenance of vampires or ghosts, for instance, but was born in visual media. On the other hand, tv shows, movies and video games are audio-visual media, and even the comic book tends to register sound in a very visceral way—Bang! Pow! Oof!—so I want to redress what I see as an imbalance and consider the very crucial role that sound plays in representing the zombie. More precisely, I want to think about how the sounds a zombie makes shape or condition its meaning for us, a meaning that is perhaps more complicated and more interesting when we do think about its vocalizations.

But I need to start with a little housekeeping: there are different kinds of zombies belonging to distinct traditions and which perform different sorts of cultural work. There are 2 primary binary oppositions that account for the various ontological, or “zontological” possibilities of the genre. Firstly, a zombie is either a supernatural object or it is a scientific object—that is to say, the zombie’s affliction either has an otherworldly, magical cause like a curse or a spell, or it has an ostensibly realistic, natural explanation like toxic waste or radiation or a virus. Secondly, the zombie is either verbal or non-verbal; it either speaks, or is capable of speech, or can understand the speech of others, or it cannot. In the case of the verbal zombie, you get an agentic figure capable of having and expressing thoughts and feelings and capable of forming attachments and developing in some way. In the case of the non-verbal zombie you have an entity that is, as philosopher David Chalmers puts it, “all dark inside.” Zombie theorists Lauro and Emby refer to the non-verbal zombie as an “anti-subject.” I just read a novel in which this kind of zombie was referred to as the “ontologically departed” (Raising Stony Marshall).

For today’s talk, I’m going to limit myself entirely to the scientific non-verbal zombie. Importantly, its in relation to this zombie type that we first see what is now the dominant zombie paradigm, that is to say the 3 Cs: Contagious Cannibals who Congregate. And its this recipe that most handily lends itself to a survivalist narrative, which is really what most zombie comics, films, shows and games are about these days.

Now it’s part of the inherently conservative nature of these narratives to construct the zombie antagonist as wholly Other. Most contemporary zombie narratives featuring the scientific non-verbal type are predicated on a categorical difference between humans and zombies. The whole point is that the zombie doesn’t count as an ethical or political subject and can be murdered with impunity. The dominant appeal of this zombie, in fact, is its mass killability. In Levinas’s terms, this zombie is an other “without a face”; an unrecognizable other, it makes no demands upon us as moral interlocutors.

Crucial to its representation in this respect is its speechlessness, its inability to engage in symbolic discourse. Not all zombies in this type experience a death of the body, but they all experience a death of self, of individual consciousness. Even in those narratives where the death of the body is ambivalent or paradoxical, the loss of subjectivity is definite and uncontentious. Over and over in the contemporary zombie narrative, the loss of consciousness, of identity, of agency is staged as loss of language.

Let me play you a sound clip from Danny Boyle’s 2002 film 28 Days Later.

This moment when an articulate loved one transforms into an inarticulate monster recurs so frequently in the zombie text that we should regard it as what Jameson calls an ideologeme, a repeatable chunk of narrative that represents the ideological kernel of a text. There is a definite social process taking place here when Selena, the second female voice you hear, says to Jim, “he’s infected” followed almost immediately by “Kill it.”

One way to read the moment of translation from human to zombie is as a collapse into animality. Indeed, the oldest and most powerful way to establish human sovereignty has been by way of a contrast with animals precisely because an animal is thought to lack the linguistic competence to say “I” and therefore be a subject with all its rights and privileges.

The concept is to some extent literalized at the level of production. While the basis of most zombie vocalizations remains the human voice, sound producers very often splice in animal noises to render those vocalizations more alien and predatory. For instance, Peter Brown who did sound design for both World War Z and A Scout’s Guide to the Apocalypse, used dogs, jaguars, wild boars, and wolves to fill out the sounds of the zombies.

In a sense, the ideologeme here is meta-ideological insofar as it establishes the conditions for politics as such. For Jacques Ranciere, politics has always been about the erection of a boundary separating the sound of “our” rational discourse from the senselessness of “their” noise. And, indeed, zombies, structurally speaking, occupy a place in narratives of besiegement that were once occupied by indigenous peoples as well as animals.

But its also true that no community can be established without boundaries of some kind. There is an obsessive but obviously practical attention in zombie narratives to the finding, constructing, and preserving of defensible barriers, where the wall or fence literally separates the human from the non-human. To the extent that the community can preserve the integrity of its borders, they can aspire to a post-capitalist and post-racial society. There’s a moment in The Walking Dead where Rick says there’s no black and white anymore, there’s only the living and the dead. Here we see the zombie helping us deliver on the promise of humanism that’s been perpetually denied by history.

But my point is that the boundary between the human community of survivors and the zombie horde is also a sonic one. It is not enough that the zombie merely lack language; the zombie has to sound its difference. So strong is the social desire to hear the zombie’s inhumanity that it overrides the fact that zombies don’t breath and therefore shouldn’t be able to produce these sounds. In other words, zombies only take air into their lungs in order to vocalize and they do so for purely artistic—that is to say cultural and political—reasons.

Let me play you some clips

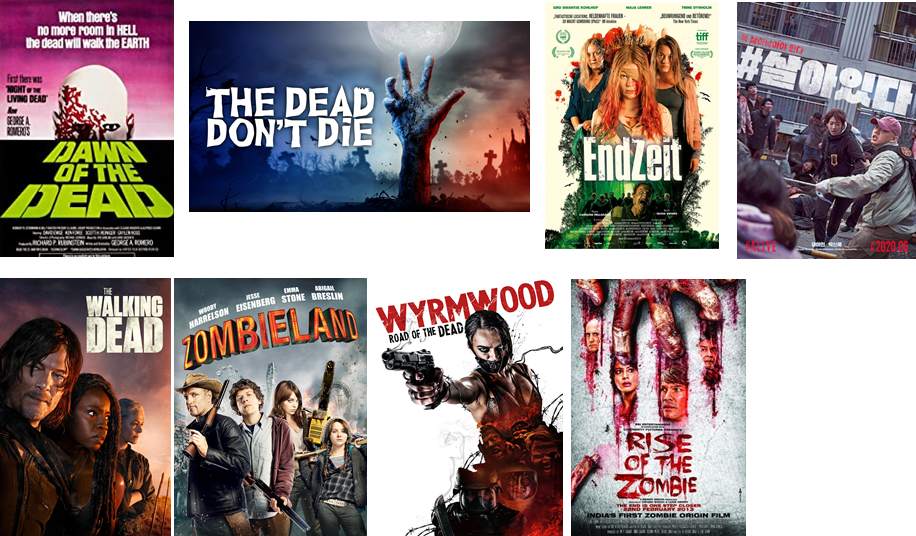

So I’ve tried to cover the gamut of zombie utterance: you’ve got your moaners, your groaners, your grunters, your growlers, your grumblers, your shriekers and your howlers. These vocalizations signify that the zombie exists beyond or rather before the usual categories of identity. For instance—we just heard male and female, adult and child, German, Korean, Australian, Indian, and American zombies, but none of those identities obtain as relevant designators for these creatures.

As the clips demonstrate, the sonic representation of zombies as “whats not whos” repeatedly depends on allusions to the animal world. At the same time, these texts rarely treat animals to the same violence that is inflicted upon the zombie. Zombies remind us of animals, but they are actually less than animals. They are less capable of communication than even the least sophisticated creatures. Ants communicate, whereas the operations of zombies are uncoordinated and entirely Newtonian, which is why they tend to collect at the bottom of hills. Leopards and wolves are capable of guile, of voluntarily suppressing their sounds when pursuing prey, but there’s something explicitly involuntary and autonomic about the zombie’s vocalizations. Animals are capable of recognizing kinship and sometimes live in highly complex social arrangements. Zombies express a negative sociality; they congregate and mass, but as atomized entities merely responding to a stimulus.

In the tradition I’m talking about, the zombie is a body without—without consciousness, without feeling, without identity. The zombie is a body without belonging. As Jeffrey Cohen writes, zombies are “nothing but their bodies.” But whose body? For all of its otherness, the zombie has a human form. There’s a paradox here: “Despite its human form,” writes Cohen, “these undead are far less anthropocentric” than other monsters. It is not despite the fact that the zombie is a human corpse that we insist on its facelessness, but because of it. Lauro and Embry write, “The zombie is the perishable carnality that we hide from ourselves, the declaration of our own thingly existence.

If as Steven Shaviro suggests, “zombies are, in a sense, all body,” that condition is recurrently expressed through sound, specifically non-semantic vocal utterances. We know from the tradition of sound poetry that the recuperation of non-semantic sounds as the stuff of oral performance is tied to a politics of reclaiming a repressed organic body. The sound poet growls and shrieks and groans and hisses in order to remind the listener that speech has its foundation in the body. The similar noises of the zombie suggest that the zombie is not merely a corporeal figure but a figure of corporeality as such. In other words, the zombie is a MEATAPHOR; it represents our carnality, the mortal corporeality we share with all living creatures, but which we denigrate and suppress as a sign of our humanity. To kill the zombie, to interrupt its noise and then to talk about it, is therefore to enforce the strictest sort of hygiene in which the human, the rational, and de-corporealized speech all line up.

And yet, and yet, the aural ecology of the zombie text contains the very elements that might allow us to disturb this hygiene in a potentially productive way. Despite the aggressive humanism of the type of zombie narrative I’m describing, there is still this tendency to strip away the veneer of civilized social discourse so as to expose the human subject in all of his/her corporeal vulnerability. In other words, Zombie narratives don’t only foreground communities and institutions under duress, but the individual human organism as a body in crisis. This body too is materialized in non-verbal sound—in grunts, screams, sobs, sudden inhalations. We heard many of these sounds in the audio I just played.

To focus on the speechified voice of the survivor is always to define the survivor as a social being whose meaning and identity derive from its participation in a definable enterprise or its membership or potential membership in what Aphonso Lingis calls the “rational community.” But to attend to the sounds that interrupt rational discourse is to discover the intimations of an ‘other’ identity and an ‘other’ community that cut across our usual categories and compartmentalizations, an identity based on what our bodies “have seen and heard, what [they] can vouch for” (Lingis “Carrion Body, Carrion Utterance”), a community that no longer excludes all those life forms which had been denied belonging for their lack of speech.

To illustrate: If we look at the first omnibus volume of Kirkman’s The Walking Dead comic, we can set what issues from the mouths of the Zombies alongside what issues from the mouths of the human survivors in moments of crisis.

Even in a work as confident in and comfortable with the categorical distinction between human and zombie as The Walking Dead, there is something inscribed here at the level of bodily sound that belies that easy confidence. Registered here in the right-hand column is a speaking of the (human) body that responds to and echoes the non-human sounds of the Zombie: indeed, at certain moments, the survivor and the zombie seem to be speaking the same (non) language (“guk”). These sounds assert a commonality that underscores the creaturely, instinctual, a-rational, animal dimension of being human that is easier to ignore when human figures appear to us as competent users of language, with articulated values and shared plans.

For Lingis, to emphasize our own carrion bodies is to discover our commonality and interdependence with non-human creatures and with the living, dying world as a whole. But Zombies are not alive and they do not die, but merely cease. I said we can think of Zombies as being all body. But it may be just as true to say that a Zombie has no body as such, since it cannot experience pain or pleasure. David Appelbaum aligns bodily sounds and vocal noisemaking with “[t]he corporeal intelligence [that] knows directly of creaturely death with its power to interrupt life at any stroke” (11). In sounds like “guk” or “gaahh” or “yeargh,” Lingis and Appelbaum hear the call of mortality, a reminder of death that the mainstream tradition of Western metaphysics, with its emphasis on communicative speech and reason, has sought to repress. In the Zombie’s “guk” we are reminded of our own creaturely, corporeal existence. But our possible kinship with the Zombie is constrained, necessarily, by its inorganicism: the Zombie is body without “susceptibility,” and where there is no precarity there is no life either.

From the perspective of the sounding body, there is still a line to be drawn between humans and Zombies, and if one shows up on your doorstep, you should definitely kill it.

But this boundary has a new logic; it no longer separates consciousness from unconsciousness, speech from non-speech, rational being from non-rational being, but differentiates between bodies that suffer and delight and bodies that don’t, bodies that can give and receive comfort and bodies that can’t, bodies that die and bodies that don’t. If there is a value in the possibility of our thinking this way, it has to do with our capacity to imagine our kinship with the plurality of living beings outside the limited humanist community of speech and reason. But additionally: to think community up from the precarious but joyful body instead of down from the abstractions of national, ethnic, racial or ideological identity is also to put in doubt the politics of the survivalist narrative in which human beings battle each other with almost as much enthusiasm as they kill the zombie.